Priscilla: Christian, wife of a Jewish freedman, fellow worker with Paul, teacher of teachers, church planter — and author of the Epistle to the Hebrews, (a letter whose writer’s name is mysteriously absent)? Was Priscilla one of the most successful teachers, evangelists, and writers in the early church? A survey of Priscilla’s ministry in Rome, Corinth, and Ephesus reveals a woman whose abilities and life’s circumstances beg the question: Was it Priscilla who wrote Hebrews?

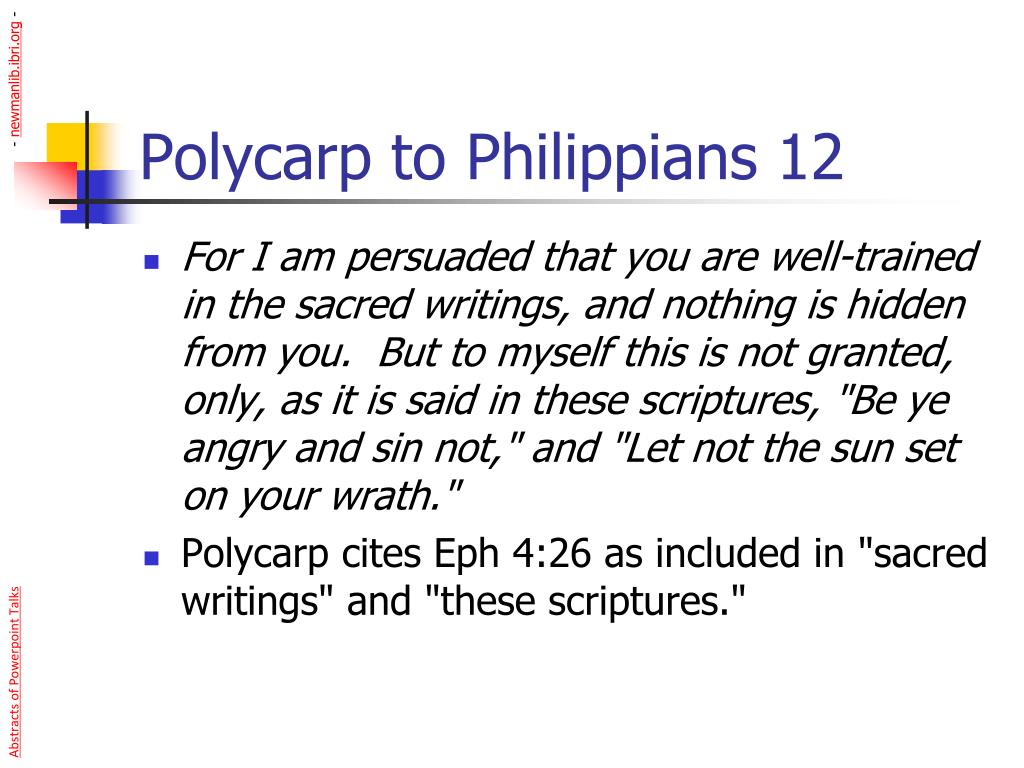

The letter itself does not indicate who the writer was. Yet, for the most part, the church has ascribed the letter to the apostle Paul. While some have suggested Luke as the writer, others have attributed the letter to Apollos, Barnabas, Clement of Rome, Timothy, Epaphras, Silas, and Philip—just to name a few. Apollos has found favor with some modern scholars. Martin Luther believed Apollos was the author. Apollos was “mighty in the Scriptures” and he “refuted the Jews in public, demonstrating by the Scriptures that Jesus was the Christ” (Acts 18:24-28). This seems to be a description of the Book of Hebrews. Apollos was a self-assured teacher driven by a spiritual quest. He landed in Ephesus and headed for the synagogue. He wanted to teach on the messianic promise and to inform and convince his hearers of the coming Messiah. He was a cultured an articulate speaker, mesmerizing his audiences everywhere. Steeped in scripture, he won their respect. Apollos was a learned man and an eloquent speaker. He may have been proficient in teaching “wisdom” in the allegorical style of Philo, who was a Jewish philosopher living in Alexandria and a great intellectual teacher. Apollos came from an environment that was conducive to studying and learning the Scriptures.

Archaeological and Literary Evidence

Archaeological research suggests that someone named Priscilla held a position of tremendous honor in the early church. Her name was found inscribed on Roman monuments, churches, and on an ancient Roman burial site called the Coemeterium Priscillae. One of the earliest churches in Rome was known as the “Titulus of St. Priscilla.” Moreover, a woman named Priscilla was said to have been burned to death in the Ostia Way, and was buried in what was later discovered as the Church of St. Prisca. This story was compiled in a 10th century work known as the Acts of St. Prisca.1 These ancient remembrances indicate that someone named Priscilla had an impressive impact on the early church.

Background in Rome

Priscilla of Scripture was most probably born a Roman Gentile who later married a Jew, as emphasized by Luke who “used an unusual order of words in Acts 18:2 in order to call attention to the fact that Priscilla, unlike her husband, was not Jewish.”2 In 49/50 A.D. the Jews were banished from Rome by decree of the Roman emperor Claudius, perhaps as a result of flaring disputes over the teachings of Christ.3 Although there is no evidence that Priscilla and Aquila were directly involved in the disruption, they did leave Rome, arriving in Corinth about 51 A.D.

Corinth

Like Priscilla and Aquila, the apostle Paul had also recently arrived in Corinth, apparently in need of employment. Scripture indicates not that Pricilla and Aquila were Christians and hence Paul’s visit, but rather that Paul went to see them because they were tentmakers. Scholars posit that Pricilla and Aquila were Christians at the time of Paul’s visit, as Paul does not mention leading them to faith, and it is unlikely that unbelieving Jews would reside with believing Jews. Over the next eighteen months Paul, Pricilla, and Aquila shared tent-making, their faith in Christ, and, perhaps along with Timothy, developed a plan to evangelize and church-plant not only in Corinth, but in Ephesus and Rome as well. By the spring of 52 A.D. Paul, Pricilla and Aquila set sail for Ephesus where Pricilla distinguished herself as a gifted teacher.

Ephesus

Shortly after arriving in Ephesus, Pricilla and Aquila met the brilliant and eloquent Apollos. Apollos had been preaching the baptism of John with great success, yet his understanding of redemption was somehow incomplete. Luke does not inform the reader of the content of Pricilla’s teaching, only that Apollos was in need of further guidance. With Priscilla’s instruction, Apollos’ message was made complete. As is confirmed by the influence her student achieved in the early church, Pricilla proved herself a successful instructor.

It is crucial to notice the subtle yet astounding information Luke provided when he recorded a woman guiding one of the most noted teachers in the early church. One must not overlook the key fact that Apollos accepted Priscilla’s instruction without reservation. Moreover, neither Luke nor Paul criticize Pricilla for having taught a man. If Pricilla had violated Paul’s Alleged prohibition against the teaching ministry of women it seems likely that either Luke or Paul would have criticized her for having taught a man. Neither Paul nor Luke hesitate to condemn misconduct among members of the church (Acts 5:1-11). But far from condemning Pricilla, both Luke and Paul promote Pricilla as one “who explained the way of God more accurately” (Acts 18:26).

Return to Rome and Ephesus

After the death of Claudius, Pricilla and Aquila returned to Rome. It is uncertain how long they remained in Rome before they journeyed back to Ephesus, for what appears like a visit rather than a permanent relocation (2 Timothy 4:19). Were Pricilla and Aquila returning to a church they had planted and continued to function in as patrons? In any case Paul recalls how this couple had achieved a substantial reputation among the Gentile churches (Romans 16:3).

Author of the Epistle to the Hebrews

How is it possible that an Epistle such as Hebrews should lack a prescript indicating both the author and the city or persons to whom the letter was addressed? “This is one of the strangest facts in all literature, that the author of so important a document as this should have left no trace of his name upon church history... It is strange enough that any epistle in the New Testament should be anonymous, but that this masterpiece among the epistles (is anonymous), seems doubly strange.”4

Possible Authors Considered

The mystery concerning the author of Hebrews has intrigued the scholarly community, beginning with the Church Fathers. Tertullian attributed the Epistle to Barnabus, though Origen and Clement argued for Paul or Luke, while Luther supported Apollos.5

Scholars rarely attribute Hebrews to Paul primarily because the letter lacks both the traditional Pauline pre and post scripts, as well as the usual Pauline method of exhortation and argument. Further evidence against Paul involves the statement “this salvation ... was confirmed to us by those who heard him” (Hebrews 2:3-4). Paul is unlikely to make this comment, as he consistently reminded his readers that he received the gospel directly through special revelation.

F.F. Bruce suggested that Apollos may have written Hebrews,6 but the obvious question remains: What possible reason would Apollos have for not signing his name? The evidence leans away from Apollos not only because the Epistle does not bear his signature, but because his conversion is unlikely to be that described in Hebrews 2:3.

Priscilla the Author of Hebrews: Feminine Images and Illustrations

Would not a woman be inclined to empathize with the struggles of other women? Hebrews 11 extols a catalog of faith heroes among whom three women are mentioned v.11, 31, 35. But one commentator has observed that the feminization of Hebrews 11 is actually more extensive once the reader notices the “roll of saints changes into a roll of virtues of saints; the names of the heroes and heroines are dropped, and their deeds only are commemorated.”7

For example, most readers agree that it was Daniel “who shut the mouths of lions, quenched the fury of the flames.” Similarly, some suggest that it was Judith who as alluded to in Hebrews 11:34, “strengthened by the grace of God have performed many manly deeds. The blessed Judith ... went forth and exposed herself to peril ... for love of country, the Lord delivered Hologemes into the hand of a woman.”8

An Exile Speaks

Does Priscilla draw parallels between her experiences as a Roman exile in Corinth and Ephesus, and the exiles in Hebrews 11? Hebrews 11 recounts the exile of Sarah, Abraham, Joseph, Moses, and the children of Israel who wandered in deserts and mountains, and in caves and holes in the ground. Through personal experience Priscilla would have understood the challenge presented by a strange land and the need for a strong faith during forced exile

Food Taboos and Strange Teachings

“Do not be carried away by all kinds of strange teachings. It is good for your hearts to be strengthened by grace, not by ceremonial foods, which are of no value to those who eat them” (Hebrews 13:9).

It can be argued that Hebrews 13:9 served not only as a warning against a particular form of apostasy, but also reflects the mind of a Roman who would have found the preparation of Kosher food not only culturally strange, but arduous as well.

Jewish Ritual and Temple Worship

Further support for a non-Jewish, non-male author arises from the curious fact that the author never mentioned the temple in Jerusalem, but rather refers only to the tabernacle. Perhaps the author had never been to Jerusalem? One could argue that this was the assumed context of the readers, but the text lacks specific details of Jewish worship, further indicating an unfamiliarity akin more to a non-Jew, non-male author.

Use of “I” and “We”

The brilliant theologian Dr. Harnack asserted that the author’s frequent use of the communicative “we” teaches, among other things, that there is possibly more than one author. It is assumed that the readers “must have known at once who was meant.”9 “Without emphasizing the change, the writer glides from “we” to “I.”10At times the author uses a cordial “we,” and moves effortlessly to an authoritative “I,” indicating the author’s position as leader. “Prisca and Aquila, as husband and “wife, and through their common labors, praised by Paul and Luke, correspond so splendidly to these conditions as no other conceivable interpretation.”11

Gospel Confirmed by Those Who Heard

“This salvation, which was first announced by the Lord, was confirmed to us by those who heard him” (Hebrews 2:3). Priscilla and Aquila’s faith was confirmed by Paul, who had received the gospel by special revelation.

The Pauline Circle

The author of Hebrews was probably among Paul’s more intimate co-workers, some of whom he introduced in Romans 16. Ten of the twenty-nine names mentioned are women, and Priscilla is the only one mentioned elsewhere in the New Testament. Moreover, Priscilla is called fellow worker or synergos, a term used by Paul to designate leaders.12 Priscilla is not the least among her fellow synergos, as “all the churches of the Gentiles are grateful to her” and when apart from Priscilla and Aquila, Paul sends his greetings and appreciation (1 Cor. 16:19, Rom. 16:3-5), referring affectionately to Prisca with the diminutive Priscilla.

The author of Hebrews had been closely associated with Timothy (Hebrews 13:23). Priscilla, Aquila, and Timothy ministered together with Paul in Corinth, and Priscilla and Aquila worked alongside Timothy in Ephesus. There can be no doubt that Priscilla and Aquila were vital members of the Pauline circle, and partners in ministry with Timothy.

The Epistle Of Apollos The Prophetrejected Scriptures Verse

Both Paul and Luke attach some sort of significance to Priscilla by virtue of placing her name first in four of the six Biblical references to Priscilla and Aquila. The prominence given to Priscilla must not be considered inconsequential, and is further evidence of the respect Paul had for his co-worker.

Chrysostom suggested that it was because of Priscilla’s superior Christian character that she preceded Aquila in four of the six Biblical references. He wrote, “...for he did not say, ‘Great Aquila and Priscilla’ but ‘Priscilla and Aquila.’ He does not do this without a reason, but he seems to me to acknowledge a greater godliness for her than for her husband... She took Apollos, an eloquent man and powerful in the scriptures, but knowing only the baptism of John; and she instructed him in the way of the Lord and made him a teacher brought to completion.”13

Scholarship and the Epistle to the Hebrews

Biblical scholars argue that Hebrews was written by a highly educated teacher, one who was well acquainted with the various philosophical debates of the day. As evidence of Priscilla’s skill, Luke did not hesitate to record her capabilities as a teacher of the great orator Apollos. Moreover, because Priscilla had ministered in three great Roman centers as an apologete and church planter, she was likely skilled in leading to Christ those who had been deceived by the popular religious competitors to Christianity. Having lived and worked among these churches as a leader and patron, Priscilla had a burden for their safety and success. What better way to ensure the advantage of these churches than to pen an Epistle for the guidance and exhortation of her leaders?

Evidence of Suppression

According to Hamack, women teachers in the early church soon came under attack. Hamack had the opportunity to examine two early manuscripts (Greek capital letter text, and a Syro-Latin Recension and Cod. D), and discovered that Priscilla’s prominent position had been suppressed by a later interpolator. Hamack found that in Acts 18:26 Aquila’s name had been placed before Priscilla and in three different places Aquila’s name was inserted without Priscilla’s.14 After reviewing these ancient manuscripts Hamack made the following conclusion; “It is quite certain that the interpolator, taking up his corrections in the first third of the second century, suppressed Prisca’s authority, placing Aquila above her in converting Apollos, and withdrew from them a letter they had written. Thus it is proven that a tendency existed at that time to weaken the remembrance of Prisca’s significance, or to destroy it vigorously.”15

Conclusion

The Epistle Of Apollos The Prophetrejected Scriptures Study

Of the many attempts to identify the author of Hebrews, Priscilla can be overlooked, and yet she remains an obvious candidate: Priscilla, a Roman Christian, a co-worker with Paul and Timothy, a woman who had not seen the Lord Jesus but had received confirmation of salvation by those who had; Priscilla, pious and wise, a church planter who was familiar with the struggles of Gentiles, exiles, and women; Priscilla, a teacher of teachers, whose name was female enough to pose a threat to a later interpolator unsympathetic with the authority and approval a woman such as she had enjoyed.

As our Lord rode triumphantly into Jerusalem, and the crowds praised God joyfully, the Pharisees insisted Jesus silence them. Jesus replied, “I tell you, if these were silent, the stones will cry out.” In some small way the stones have cried out on behalf of Priscilla. Monuments, churches, burial grounds, and the ‘Acts of Prisca’ are faint yet persistent echoes of a faithful woman.

If neither Luke or Paul were unwilling to silence the work of a woman such as Prisca, dare we?

Notes

The Epistle Of Apollos The Prophetrejected Scriptures In The Bible

- Lois Dickie, No Respecter of Persons, (Pompano Beach, Florida: Exposition Press, 1985), p. 185.

- Ibid. p. 142.

- Flavius Josephus, Complete Works, (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1960), xviii.3.5.

- Lee Anna Starr, The Bible Status of Women, (New York: Revell Co. 1926), p. 204.

- The New Bible Dictionary, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1979), p. 512-513.

- F.F. Bruce, The Pauline Circle, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing Co., 19779), p. 57.

- Rendel J. Harris, Side-Lights on the Authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews, (London: Kingsgate Press, Jamesclarke & Co., 1906), p. 166.

- Ibid. p. 170-171.

- Lee Anna Starr, The Bible Status of Women, (New York: Revell Co., 1926), p. 402.

- Ibid.p.411.

- Ibid. p. 411.

- David Scholer, “Paul’s Women Coworkers” Daughters of Sarah Vol. 6 (July/August 1980), p. 3-6.

- John Chrysostom, First Sermon on the Greeting to Priscilla and Aquila, Migne, Patrologia Graeca 51.187. Translated by Catherine Kroeger, Priscilla Papers, Summer 1991.

- Lee Anna Starr, The Bible Status of Women, (New York: Revell Co., 1926), p. 413.

- Ibid. p. 413.